Adafruit gfx graphics library

Overview

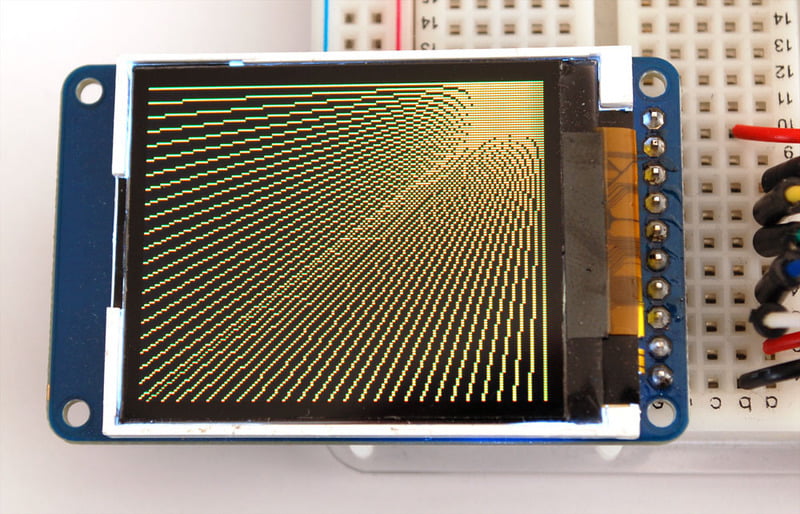

The Adafruit_GFX library for Arduino provides a common syntax and set of graphics functions for all of our LCD and OLED displays. This allows Arduino sketches to easily be adapted between display types with minimal fuss…and any new features, performance improvements and bug fixes will immediately apply across our complete offering of color displays.

The Adafruit_GFX library can be installed using the Arduino Library Manager…this is the preferred and modern way. From the Arduino “Sketch” menu, select “Include Library” then “Manage Libraries…”

Type “gfx” in the search field to find it quickly:

While you’re there, also look for and install the Adafruit_ZeroDMA library.

The Adafruit_GFX library always works together with an additional library unique to each specific display type — for example, the ST7735 1.8" color LCD requires installing Adafruit_GFX, Adafruit_ZeroDMA and the Adafruit_ST7735 library. The following libraries now operate in this manner:

- RGBmatrixPanel, for our 16x32 and 32x32 RGB LED matrix panels.

- Adafruit_TFTLCD, for our 2.8" TFT LCD touchscreen breakout and TFT Touch Shield for Arduino.

- Adafruit_HX8340B, for our 2.2" TFT Display with microSD.

- Adafruit_ST7735, for our 1.8" TFT Display with microSD.

- Adafruit_PCD8544, for the Nokia 5110/3310 monochrome LCD.

- Adafruit-Graphic-VFD-Display-Library, for our 128x64 Graphic VFD.

- Adafruit-SSD1331-OLED-Driver-Library-for-Arduino for the 0.96" 16-bit Color OLED w/microSD Holder.

- Adafruit_SSD1306 for the Monochrome 128x64 and 128x32 OLEDs.

The libraries are written in C++ for Arduino but could easily be ported to any microcontroller by rewriting the low-level pin access functions.

The Old Way

Older versions of the Arduino IDE software require installing libraries manually; the Arduino Library Manager did not yet exist. If using an early version of the Arduino software, this might be a good time to upgrade. Otherwise, this tutorial explains how to install and use Arduino libraries. Here are links to download the GFX and ZeroDMA libraries directly (use the links above to get the corresponding display-specific libraries)

Coordinate System and Units

Pixels — picture elements, the blocks comprising a digital image — are addressed by their horizontal (X) and vertical (Y) coordinates. The coordinate system places the origin (0,0) at the top left corner, with positive X increasing to the right and positive Y increasing downward. This is upside-down relative to the standard Cartesian coordinate system of mathematics, but is established practice in many computer graphics systems (a throwback to the days of raster-scan CRT graphics, which worked top-to-bottom). To use a tall “portrait” layout rather than wide “landscape” format, or if physical constraints dictate the orientation of a display in an enclosure, one of four rotation settings can also be applied, indicating which corner of the display represents the top left.

Also unlike the mathematical Cartesian coordinate system, points here have dimension — they are always one full integer pixel wide and tall.

Coordinates are always expressed in pixel units; there is no implicit scale to a real-world measure like millimeters or inches, and the size of a displayed graphic will be a function of that specific display’s dot pitch or pixel density. If you’re aiming for a real-world dimension, you’ll need to scale your coordinates to suit. Dot pitch can often be found in the device datasheet, or by measuring the screen width and dividing the number of pixels across by this measurement.

For color-capable displays, colors are represented as unsigned 16-bit values. Some displays may physically be capable of more or fewer bits than this, but the library operates with 16-bit values…these are easy for the Arduino to work with while also providing a consistent data type across all the different displays. The primary color components — red, green and blue — are all “packed” into a single 16-bit variable, with the most significant 5 bits conveying red, middle 6 bits conveying green, and least significant 5 bits conveying blue. That extra bit is assigned to green because our eyes are most sensitive to green light. Science!

For the most common primary and secondary colors, we have this handy cheat-sheet that you can include in your own code. Of course, you can pick any of 65,536 different colors, but this basic list may be easiest when starting out:

- // Color definitions

- #define BLACK 0x0000

- #define BLUE 0x001F

- #define RED 0xF800

- #define GREEN 0x07E0

- #define CYAN 0x07FF

- #define MAGENTA 0xF81F

- #define YELLOW 0xFFE0

- #define WHITE 0xFFFF

For monochrome (single-color) displays, colors are always specified as simply 1 (set) or 0 (clear). The semantics of set/clear are specific to the type of display: with something like a luminous OLED display, a “set” pixel is lighted, whereas with a reflective LCD display, a “set” pixel is typically dark. There may be exceptions, but generally you can count on 0 (clear) representing the default background state for a freshly-initialized display, whatever that works out to be.

raphics Primitives

Each device-specific display library will have its own constructors and initialization functions. These are documented in the individual tutorials for each display type, or oftentimes are evident in the specific library header file. The remainder of this tutorial covers the common graphics functions that work the same regardless of the display type.

The function descriptions below are merely prototypes — there’s an assumption that a display object is declared and initialized as needed by the device-specific library. Look at the example code with each library to see it in actual use. For example, where we show print(1234.56), your actual code would place the object name before this, e.g. it might read screen.print(1234.56) (if you have declared your display object with the name screen).

The function descriptions below are merely prototypes — there’s an assumption that a display object is declared and initialized as needed by the device-specific library. Look at the example code with each library to see it in actual use. For example, where we show print(1234.56), your actual code would place the object name before this, e.g. it might read screen.print(1234.56) (if you have declared your display object with the name screen).

Drawing pixels (points)

First up is the most basic pixel pusher. You can call this with X, Y coordinates and a color and it will make a single dot:

- void drawPixel(uint16_t x, uint16_t y, uint16_t color);

- void drawLine(uint16_t x0, uint16_t y0, uint16_t x1, uint16_t y1, uint16_t color);

For horizontal or vertical lines, there are optimized line-drawing functions that avoid the angular calculations:

- void drawFastVLine(uint16_t x0, uint16_t y0, uint16_t length, uint16_t color);

- void drawFastHLine(uint8_t x0, uint8_t y0, uint8_t length, uint16_t color);

Rectangles

Next up, rectangles and squares can be drawn and filled using the following procedures. Each accepts an X, Y pair for the top-left corner of the rectangle, a width and height (in pixels), and a color. drawRect() renders just the frame (outline) of the rectangle — the interior is unaffected — while fillRect() fills the entire area with a given color:

- void drawRect(uint16_t x0, uint16_t y0, uint16_t w, uint16_t h, uint16_t color);

- void fillRect(uint16_t x0, uint16_t y0, uint16_t w, uint16_t h, uint16_t color);

To create a solid rectangle with a contrasting outline, use fillRect() first, then drawRect() over it.

Circles

Likewise, for circles, you can draw and fill. Each function accepts an X, Y pair for the center point, a radius in pixels, and a color:

- void drawCircle(uint16_t x0, uint16_t y0, uint16_t r, uint16_t color);

- void fillCircle(uint16_t x0, uint16_t y0, uint16_t r, uint16_t color);

Rounded rectangles

For rectangles with rounded corners, both draw and fill functions are again available. Each begins with an X, Y, width and height (just like normal rectangles), then there’s a corner radius (in pixels) and finally the color value:

- void drawRoundRect(uint16_t x0, uint16_t y0, uint16_t w, uint16_t h, uint16_t radius, uint16_t color);

- void fillRoundRect(uint16_t x0, uint16_t y0, uint16_t w, uint16_t h, uint16_t radius, uint16_t color);

Here’s an added bonus trick: because the circle functions are always drawn relative to a center pixel, the resulting circle diameter will always be an odd number of pixels. If an even-sized circle is required (which would place the center point between pixels), this can be achieved using one of the rounded rectangle functions: pass an identical width and height that are even values, and a corner radius that’s exactly half this value.

Triangles

With triangles, once again there are the draw and fill functions. Each requires a full seven parameters: the X, Y coordinates for three corner points defining the triangle, followed by a color:

- void drawTriangle(uint16_t x0, uint16_t y0, uint16_t x1, uint16_t y1, uint16_t x2, uint16_t y2, uint16_t color);

- void fillTriangle(uint16_t x0, uint16_t y0, uint16_t x1, uint16_t y1, uint16_t x2, uint16_t y2, uint16_t color);

Characters and text

There are two basic string drawing procedures for adding text. The first is just for a single character. You can place this character at any location and with any color. There’s only one font (to save on space) and it’s meant to be 5x8 pixels, but an optional size parameter can be passed which scales the font by this factor (e.g. size=2 will render the text at 10x16 pixels per character). It’s a little blocky but having just a single font helps keep the program size down.

- void drawChar(uint16_t x, uint16_t y, char c, uint16_t color, uint16_t bg, uint8_t size);

Text is very flexible but operates a bit differently. Instead of one procedure, the text size, color and position are set up in separate functions and then the print() function is used — this makes it easy and provides all of the same string and number formatting capabilities of the familiar Serial.print() function!

- void setCursor(uint16_t x0, uint16_t y0);

- void setTextColor(uint16_t color);

- void setTextColor(uint16_t color, uint16_t backgroundcolor);

- void setTextSize(uint8_t size);

- void setTextWrap(boolean w);

Begin with setCursor(x, y), which will place the top left corner of the text wherever you please. Initially this is set to (0,0) (the top-left corner of the screen). Then set the text color with setTextColor(color) — by default this is white. Text is normally drawn “clear” — the open parts of each character show the original background contents, but if you want the text to block out what’s underneath, a background color can be specified as an optional second parameter tosetTextColor(). Finally, setTextSize(size) will multiply the scale of the text by a given integer factor. Below you can see scales of 1 (the default), 2 and 3. It appears blocky at larger sizes because we only ship the library with a single simple font, to save space.

Note that the text background color is not supported for custom fonts. For these, you will need to determine the text extents and explicitly draw a filled rectangle before drawing the text.

After setting everything up, you can use print() or println() — just like you do with Serial printing! For example, to print a string, use print("Hello world") - that’s the first line of the image above. You can also use print() for numbers and variables — the second line above is the output ofprint(1234.56) and the third line is print(0xDEADBEEF, HEX).

By default, long lines of text are set to automatically “wrap” back to the leftmost column. To override this behavior (so text will run off the right side of the display — useful for scrolling marquee effects), use setTextWrap(false). The normal wrapping behavior is restored with setTextWrap(true).

See the “Using Fonts” page for additional text features in the latest GFX library.

Bitmaps

You can draw small monochrome (single color) bitmaps, good for sprites and other mini-animations or icons:

- void drawBitmap(int16_t x, int16_t y, uint8_t *bitmap, int16_t w, int16_t h, uint16_t color);

This issues a contiguous block of bits to the display, where each '1' bit sets the corresponding pixel to 'color,' while each '0' bit is skipped. x, y is the top-left corner where the bitmap is drawn, w, h are the width and height in pixels.

The bitmap data must be located in program memory using the PROGMEM directive. This is a somewhat advanced function and beginners are best advised to come back to this later. For an introduction, see the Arduino tutorial on PROGMEM usage.

Clearing or filling the screen

The fillScreen() function will set the entire display to a given color, erasing any existing content:

Download: file

Copy Code

void fillScreen(uint16_t color);

Download: file

Copy Code

void fillScreen(uint16_t color);

0 comentarios:

Publicar un comentario